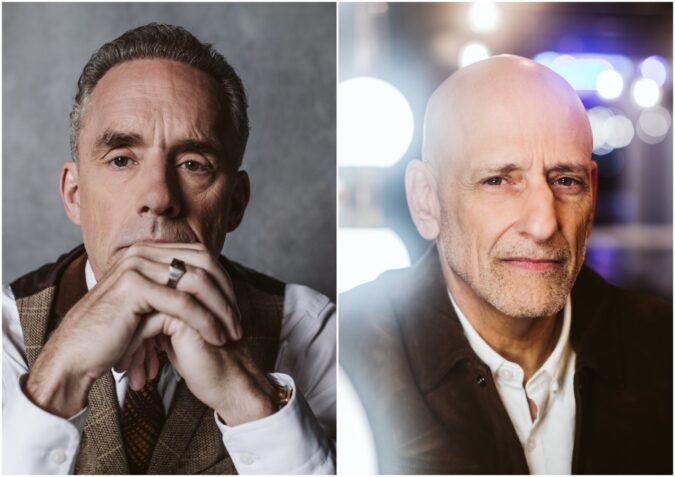

The following is a transcript excerpt from Dr. Jordan Peterson’s conversation with Andrew Klavan on how coming to know God over time develops an experiential relationship and why the journey toward the self you were made to be is a joyful journey. You can listen to or watch the full podcast episode on DailyWire+.

Start time: 1:28:08

Andrew Klavan: This is one of the problems I’ve always had with the postmodernists: They talk about the meaninglessness of language, but I understand what they’re saying. And so obviously — except with Derrida, who had the integrity to write absolute gibberish — they actually are disproving their own point. And they talk about, basically, the fact that we can’t know anything, but we can. We can know if I go north, I get to Canada; if I go south, I get to Mexico.

Jordan B. Peterson: Right. We cannot know anything purely by words.

Andrew Klavan: Yes, that’s right. And so I really did have some kind of trust in myself. I simply could not break through my milieu, which was so default at least agnostic and really atheistic. The other thing about this, too, by the way, is being a bit of a tough guy, I thought that, in my misery when I cracked up, to embrace God, even though it was logical, was a crutch. How would I know whether I had embraced him in reality or just because I wanted to get out of this incredible pain I was in? And so I couldn’t do it.

When, years later, I was now a very happy person, my career took off, everything started to go right, I still had that logic and something else was true as well, which was that I had been a real Freudian. I had grown up in that real core Freudian world where all the art stank because everybody’s trying to prove your mother was to blame for everything and all that. And I didn’t come to feel that what Freud said was utter nonsense; I came to feel that the details of what he said were utter nonsense, that the structure of the relationship between a therapist or a mentor and a client or a son or a friend or whatever, I thought he got a lot of that quite right — the idea of transference and all this — which made me feel that all of the insights I had had in therapy that I thought were salvific had not been.

What had been salvific was the loving relationship I had had with this older man who had taken the place of a father who had not been very helpful and it was actually the love that had saved me, and I began to believe in psychology.

Jordan B. Peterson: Well, that is that relationship again.

WATCH: The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast on DailyWire+

Andrew Klavan: Yes. And it made me feel that psychology is a story, that stories give us the ability to take the ineffable and move it around a little bit. And so you split up things that are actually unified into pieces that you can move. And that brought me back to God.

And ultimately, it comes back to fiction again and how much I love fiction. I was reading. I don’t know if you’ve ever read the Patrick O’Brien novels? They’re just wonderful seafaring adventure stories about the Napoleonic wars. They’re absolutely brilliant.

Jordan B. Peterson: No, no. I do not know of them.

Andrew Klavan: In them, there’s a very intellectual character named Maturin who’s an ugly little man but very brilliant and kind of a spy. I kind of admired him and identified with him a little bit. He’s a Catholic, and there’s a scene where he was falling asleep, and the line is: He said a prayer and went to sleep. And I was reading in bed and I thought, well, if Maturin can say a prayer before he goes to sleep, so can I.

And I just thanked God for the journey I had come out of — this horrible darkness that I thought was the end. I thought I was going to kill myself. Instead, I had come out, and here I was now. I had two children. My career was great. I was so happy to be with my beloved wife. I was living in a wonderful place. And I thanked God, and it changed my life. I woke up the next morning, and everything was brighter. Everything was clearer — the details of life. I christened it the joy of my joy.

Jordan B. Peterson: That is the definition of gratitude.

Andrew Klavan: Yes.

Jordan B. Peterson: So you pointed to three things there that we should take apart. Maybe we can close with this.

The first is, one of the primary Freudian accusations — and Marx did this too — was that religion was just a shield against death-anxiety or a sop for the victimized poor. That would be Marx. But Freud was a little bit more trenchant, saying it is a shield of meaning the weak use to protect themselves against the ultimate reality of pointless death. People like Ernest Becker made much of that in his “Denial of Death,” which is actually really a great book, even though it is fundamentally wrong. It is a great book.

But there is something really unwise about that perspective. So here are three arguments against that from someone who really admires Freud, by the way. First of all, if that was the case, why bother with hell? Because medieval people were as scared as hell of hell as modern people are of death. The evidence for that is clear. And you might say, “Well, hell was just a convenient place to put your enemies.” But that is not a good analysis. So, if it is just a death-anxiety shield, then why decorate it with this terrible moral obligation and the reality of hell? So that is a big problem for that theory.

Then you have two other problems, which is that you are supposed to hoist your cross as a Christian believer, and there literally is not anything worse than that by definition because it means you have to stand up to the mob, even if they are your brothers; that you have to forsake your family in pursuit of ethical truths; that you have to suffer torment — physical and metaphysical; and that you have to face the reality of hell itself.

So, sorry, that is not a defense against death-anxiety, not least because I think you can make a very powerful case that confronting malevolence is worse than confronting death.

Andrew Klavan: Yes.

Jordan B. Peterson: We know this because people are rarely traumatized by a brush with death, and they are routinely traumatized by a brush with malevolence. So even on those grounds, you can see that the reality of evil is more trenchant and salient than the reality of death. So that Freudian argument? It is just not right. He got that wrong.

Andrew Klavan: This is where Freud indulges in quackery a little bit. He’s interviewing, you know, 20 hysterical Victorian Viennese, and he decides that God is a projection of the father. And he says it very definitively, and you think: Hey, you’re welcome to your opinion. But really, what you’re talking about to me is like saying that you believe in bread to forestall the fear of hunger.

You know, C.S. Lewis points out that we don’t have any desires that don’t have an answer. All our desires have an answer, in fact, in the world; everything that we hunger for is actually there. And this is one of my problems with the evolutionary biologists who think that they can trace the creation of morality. My point about that is it’s like saying that because I have eyes, that I’ve invented light, you know. I’ve invented the human experience of light, perhaps, but not light itself.

And it’s the same thing with the moral sense that we have. You can say it’s a result of evolution. That’s fine. But it’s a result of evolution like the eye in relationship to something that exists, which is the moral order. And I think that these arguments really do fall apart once you begin to have a realistic view of God and not the sort of happy, you know, yellow face with a smile on it. I have to tell you that weeks after my baptism, my wife, who now knows me to my footsoles turned to me and said, you are such a different person; you are just filled with joy and relaxation. Knowing God has been joy on joy for me. I have to tell you.

This is one of the least quoted lines in the Gospel, but Jesus said, I’m telling you things so that my joy will be in you and your joy will be complete. Somehow religion manages to turn this into this tormented struggle with your sexual desires or whatever. But no, I actually do think this journey toward the self that you were made to be is a very joyful journey. And every time you take a step on it. And by “joy,” I don’t mean happiness. I don’t mean, again, that smiley face. I mean a vitality of life.

The only evidence for love is over time. Experience over time is the evidence for love. I think that’s true of God, too, ultimately. There’s no proof of God. There’s only experience over time as you get to know him, and it develops in your life — and I highly recommend that. That’s all I can say.

* * *

To continue, listen or watch more content with Dr. Jordan Peterson on DailyWire+.

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson is a clinical psychologist and professor emeritus at the University of Toronto. From 1993 to 1998 he served as assistant and then associate professor of psychology at Harvard. He is the international bestselling author of Maps of Meaning, 12 Rules For Life, and Beyond Order. You can now listen to or watch his popular lectures on DailyWire+.

Andrew Klavan is the host of “The Andrew Klavan Show” at The Daily Wire. He is the bestselling author of the Cameron Winter Mystery series. The third installment, “The House of Love and Death,” is now available. Follow him on X: @andrewklavan